Eilidh Cairns;Gary Mason; Tom Barrett; Photos from:RoadPeace; The Times; RAF

If any of the campaigns for cyclist safety are to actually achieve anything there is an absolutely central problem which needs addressing. This is the ability of the motorised to shift responsibility for their lethal behaviour on to their actual and potential victims – through the simple act of saying that they don’t “see” their victims. Below we look at two current and one recent case of cyclists killed in London .

While reading these cases, consider Rule 126 of the Highway Code:

“126: Stopping Distances: Drive at a speed that will allow you to stop well within the distance you can see to be clear.”

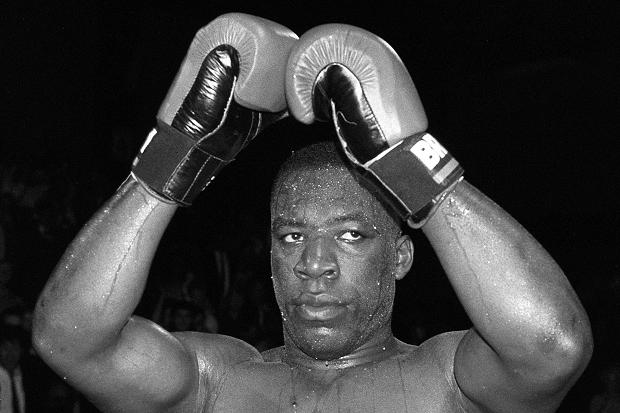

Gary Mason

The Times report of the death of Gary Mason includes:-

- Collision investigators estimated the driver had been driving at between 25mph and 48mph at the time of the crash, and he had been going at between 36mph and 41mph in the lead-up to the collision.

- He failed a police sight test on the day of the crash.

- The light on his speedometer wasn’t working.

A useful commentary is here, and I quote one section in full:

The junction in Wallington where Gary was killed is a dangerous junction because of people like this driver. They turn from Woodcote Road into Sandy Lane South, and because the junction is at a gentle angle, if there is nothing in Sandy Lane South it’s possible to cut the corner and make the turn without slowing down. On a test track, that would be the ‘racing line’ and the correct thing to do – after all, you’re in a race and supposed to be going as fast as you can. Because this is a public road, you’re not supposed to do this: there could be pedestrians crossing the road, or cyclists in the road, and at 40 MPH say, you would have little chance of avoiding them if you saw them. And at 6AM on a drizzly, dark morning such as when Gary was killed, you might not see them. Especially if your sight was defective. The road markings at the junction encourage drivers to make a proper right turn and slow down, and there are hazard lines that you’re not supposed to cross. The driver in this case said he would cut across the road markings “eight times out of 10”.

Group Captain Tom Barrett

I emphasise some parts of this report from the Uxbridge Gazette:

A van driver who mowed down and killed a senior RAF officer as he was cycling home along the A40 has been warned he faces possible jail after he was convicted of death by careless driving today (Weds).

Paul Luker, 51, claimed he was blinded by the sun when he hit Group Captain Tom Barrett, the 44-year-old Station Commander of RAF Northolt, in March last year.

Gp Capt Barrett served as an aide-de-camp to the Queen, as well as in Iraq and Afghanistan, and had been awarded an OBE.Described as an avid cyclist, he often used the journey from the base in Ruislip to his home in Beaconsfield, Bucks, as a training exercise.

He had travelled less than a mile when he was hit by Lukers transit van at 5.07pm on March 10. It took a jury of five men and seven women just two-and-a-half hours to find Luker guilty of causing death by careless or inconsiderate driving. Luker showed no emotion as the verdict was announced, while his wife wept in the public gallery. Fellow motorists told of a loud bang and a twisted wheel flying through the air after the crash.

The impact caused Gp Capt Barrett, a married father-of-two, to be thrown off his bicycle and he landed on the roadside. He was rushed to St Marys Hospital in Paddington but died from multiple injuries, Harrow Crown Court heard.

Prosecutor Adina Ezekiel said that Luker should have adapted his driving style if the conditions were poor. The prosecution are not suggesting that Mr Luker set out deliberately or maliciously to collide with Gp Capt Barretts bicycle. But the question is whether the driving was careless or inconsiderate said Ms Ezekiel.

Luker – who was driving at 50mph, under the speed limit – wept as he told how he simply could not understand why he did not see Gp Capt Barrett.

The self-employed delivery driver told how the crash had left him needing counselling and had stripped him of his happy-go-lucky personality.

Giving evidence Luker, who has been driving since 1984, said the sun had been quite low as he drove on the Greenford flyover.

“I was very short-sighted, I was struggling to see the brake lights of the car in front of me, so I decided I needed to slow down. At that point I was in the middle lane and the sun got worse, so I put a cap on but it didnt help much. The sun was as low that day as I have ever known. “The only way I could get the sun out of my eyes was to put the sun visor fully down, but I would have been blinded by that, so I put it on an angle. I could see people flashing me for going too slow so I decided to go into the inside lane and remember looking in my mirror for motorcycles. All of a sudden I felt a bump.”

Luker added: “I immediately slowed down and decided not to do an emergency brake because the car behind me was too close and stopping suddenly might have caused an accident, so I geared down. “I thought I hit a deer. I never saw anything. I saw the bicycle wheels along the road and then I realised I hit a cyclist. I remember shouting oh no, oh no, I was in some sort of shock. Mr Barrett was lying face down and I saw blood coming out of his ear and mouth and I knew at that stage it was quite a problem.”

“I just don’t understand why I didn’t see him,” he said.

“I would have done everything in my power to avoid any accident. I think about it all the time. I was a pretty happy go lucky sort of fellow until that day.”

Bailing Luker until March 26 while pre-sentence reports are prepared Judge John Anderson said: “It is common ground in this case that this was a momentary lapse of attention.”

“Sentencing guidelines recommend a community order but you must understand that this offence carries a maximum of five years imprisonment and all options are open.

“You will be disqualified from driving but I have been persuaded in these exceptional circumstances for the time being to allow you to arrange your financial affairs so this does not devastate your family. “I do this more out of mercy than anything else, but you understand that you will be disqualified for a lengthy period.”

Luker, of Beaconsfield Road, Farnham Royal, Bucks, denied causing death by careless or inconsiderate driving.

++++++

Some specific comments here:

- There is persistent reference, as in many road crashes, to the suffering of the person who was legally responsible for the death (e.g. stripped of his happy-go-lucky personality). Remorse – actual or alleged – plays a big part on affecting sentencing, which in most cases does not involve custodial sentences. While obviously an absence of remorse would be particularly anti-social, it is a feature of the legal systems treatment of road crash deaths that remorse and lack of willful intent to kill can play such a mitigating part in assessing the severity of the offence. “Road safety” is often an inversion of reality: in court it is sometimes difficult to see whether the person who was killed was the victim, or the person legally responsible for killing them.

- A persistent theme in excusing lethal driving is the “momentary lapse of attention” trope. But deaths are rarely caused by people who have been driving perfectly and just happened to have “lapsed” at the precise time when their victim happened to be in “the wrong place at the wrong time”. And in this case, according to the driver’s own account, driving while being unable to see ahead had been occurring for some time.

- The absolutely basic point here is made by the prosecuting lawyer: Luker should have adapted his driving style if the conditions were poor. This is just reiteration of the basic rule in the Highway Code, as well as simple common sense. It is worth looking at this a bit more: despite having described his inability to see where he was going, the defendant could still say in court “I just don’t understand why I didn’t see him,” and “ “I would have done everything in my power to avoid any accident” when all that was required was driving in such a way that he could see where he was going. If that was impossible, perhaps stopping driving for a while? Inconvenient, but within “everything in my power”. Some might see this simply as a psychological mechanism to deal with guilt. Cognitive dissonance or another process of defending the psyche. I think, instead, we should look at the culture which sustains these beliefs.

Eilidh Cairns

The magistrates sitting at Kingston Magistrates Court did not exercise their discretion to impose a driving ban on the 55-year-old from Dagenham.

However, just three months after the fatal incident in Notting Hill in February 2009, Lopes had failed an eye test and his driving licence was revoked. He got it back in April 2010, and returned to driving HGVs.

+++

We will look again at this case when reporting on the See Me Save Me campaign. Suffice it to say that there is in this, as the other cases, evidence of driving without being able or willing to see where the guilty driver was going.

But it is worse than that. I would argue that a key reason why motorists feel they can get away with justifying bad driving is the “Sorry Mate I Didn’t See You” (SMIDSY) excuse. (See the CTC’s campaign against SMIDSY).And this excuse is facilitated by precisely the kind of campaigns which put the onus of responsibility to “Be Seen” on the least dangerous to others, rather than requiring those who are dangerous to others to watch out for their potential victims.

The most basic rule of safe driving, in the Highway Code and elsewhere, has been to “Never drive in such a way that you can not stop within visible distance“. (In the current Highway Code this is expressed as

“126: Stopping Distances: Drive at a speed that will allow you to stop well within the distance you can see to be clear.”)

But this is eroded, not just by failure to have proper speed limits and their compliance, but by the assumption that if motorists don’t “see” their victims, it is the victim’s fault. Whether by lengthening sight lines or other measures, the underlying belief system thrusts the onus of risk on to motorists’ actual or potential victims. It is not just a lack of speed control, or the failure to weed out motorists who can’t see where they are going. It is a cultural belief that you don’t have to fulfill a responsibility to properly watch out for those you may hurt or kill. And this culture is not just colluded with, but actually promoted by a “road safety” movement with promotion of “hi-viz” to be worn by those outside cars

I emphasise “watching out for” because what is required is a thorough process where drivers consider the possible positions of those they may drive into, think about their need to avoid doing so, and drive accordingly. The image of a pedestrian or cyclist on the retina of the driver is just the first part of this process. And the key element is searching – watching out or looking out – for these people in the first place. It is an active process which is far more effective than any amount of hi-viz, which may be irrelevant anyway. I am regularly told by motorists that they see plenty of cyclists without lights at night. Indeed: if they are driving properly (albeit in an urban area with street lighting) they will indeed see unlit cyclists.

With regard to promotion of hi-viz etc., let me be quite clear: my argument is not just that this is rather unsavoury victim-blaming and morally objectionable. It is that it exacerbates the very problem it claims to address.

Meanwhile, we have campaigns for cyclist safety which don’t seem to have offered any significant attempt to address this central issue. There is no reference to even the operation of existing law, let alone changes in it, in The Times eight-point campaign. Nor in Ministerial responses to it. As usual, the gorilla in the room – danger from incorrect use of motor vehicles – is ignored.

However the highway and vehicles are engineered, drivers are likely to have the potential to hurt and kill other road users ahead of them. We need a real road safety culture, based on the principles of Road Danger Reduction, which requires them to act accordingly and not shift responsibility on to their potential or actual victims.