Dear Chancellor,

Please consider the increases in the financial costs of driving described below in your Autumn Budget 2025 for the following reasons:

- Raising significant much-needed revenue for the Exchequer.

- Sending a “price signal” to highlight the adverse consequences of driving on society, specifically public health and our local and global environments.

- Fulfilling the Government commitment to decarbonise transport and reach Net Zero requires this (amongst other measures) in the road transport sector.

- The burden of additional expenditure will fall more on the wealthier motorists. While the recommended price increases are indirect, they are only as “regressive” as the much larger tax take from VAT, and will be paid more by people with greater personal income and wealth.

- You will not be breaking any promises not to raise VAT or income tax.

- Reducing the amount of driving through raising the cost of driving to motorists reduces the need for more road building, thus saving the Exchequer the massive financial burden involved.

Below I describe the background to this issue and the justifications for significant increases in the cost of driving to motorists.

Revenue raised from driving

(Note that all figures below are approximate and refer mainly to car and van drivers. Exceptions may have to be made for some necessary road freight deliveries and types of drivers such as low-income drivers in rural areas dependent on car transport, some people with disabilities etc.)

It must be emphasised that as a proportion of economic activity subject to taxation (in 2024/25, the UK’s public sector current receipts were approximately £1,136 billion), or Gross Domestic Product (of c. £3 trillion), the tax take from private motoring is small: there are expected revenues of £24.4billion from fuel duty in 2024-25, with a halving from EVs replacing ICE cars and vans likely by the 2030s, and receipts close to zero by 2050. Additional forms of taxation are VED – £8.4 billion in 2024/25 – and VAT on new cars and fuel. These raise total taxation on private motoring to between £35 and 40 billion per year. (The higher amount includes road freight, taxis etc.).

This means that car and van drivers only pay some 3% of the annual tax take, and 1.2% of GDP, despite car and van usage being a major expense for car/van users.

The “regressive tax” issue

Fuel duty and the proposed per-mile tax on electric vehicles are not, strictly speaking “regressive” as they are not imposed in such a manner that the tax rate decreases as the amount subject to taxation increases. Nevertheless, there is a legitimate concern that people on lower incomes will pay a higher proportion of their disposable income on driving with such taxes. This is largely misplaced, as the poorest (especially in urban areas) either don’t drive or drive less than wealthier motorists.

Besides, if there is opposition to paying any form of tax which is not “progressive”, you would have to cancel or at least reduce Value Added Tax (VAT), which brings over £170 billion annually to the Exchequer. In addition, paying for driving can be morally justified by the massive external costs of driving – “polluter pays” is a idea well-understood by the public, and can be applied here.

“Polluter pays” and the external costs of driving

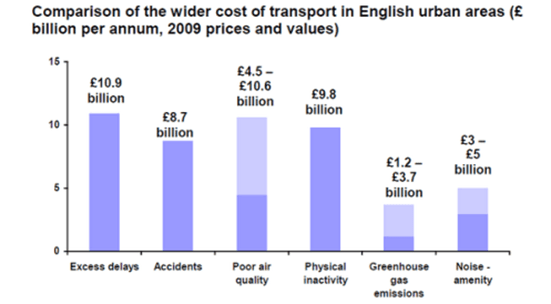

There are significant moral issues around assigning economic costs to matters such as the costs of road crashes, deaths and poor health from bad air quality etc. Nevertheless, economists in the Department for Transport and elsewhere calculate such costs. These “external costs” of driving are valued at significantly more than the tax revenue obtained from drivers, even in cost-benefit analyses and conventional economics, for example as shown in this academic study from 2012.

Or you can look at the report from November 2009, by the four relevant Government Departments (Health, Transport, Environment, Communities and Local Government) and the Cabinet Office: “ The wider costs of transport in English urban areas in 2009” which showed tax revenues significantly below the external costs to society, meaning in effect that driving receives a net subsidy, rather than taxation.

Here is the graphic presentation of the report:

Note that over the last 16 years these costs will have generally increased, with greenhouse gas emissions in particular costing more. Furthermore, other costs are not mentioned:

- Road Danger – which is different from the aftermath of crashes (not “accidents”) – dissuades parents from allowing their children to walk and cycle as well as intimidating actual and potential users of Active Travel.

- Space consumption by parked cars prevents more benign uses of land.

such as housing, or much-needed green space in deprived areas. - Road building costs a great deal economically as well as environmentally.

Or you can look at mainstream think tanks, such as in this report from the IPPR in 2012 saying:

“Put simply, there is no war on motorists. Fuel duty and VED are both effective and justifiable motoring taxes that not only encourage greater fuel efficiency but go some way to offsetting the environmental and social costs of motoring. Recent government reductions or delays to planned increases in fuel duty in particular are not justified in terms of sound public policymaking.”

“This paper has examined the claims that motoring taxes are too high and that insufficient revenue from them is spent on roads. We conclude that neither is true.”

Or consider opposition to increasing subsidy to drivers in 2014 by one of your predecessors, Mr Osborne, here.

You can also compare the costs of driving (to the user) to those of public transport, particularly bus and coach use.

All this provides you with economic justification for significant increases in the price of driving.

Furthermore, any serious attempts to counter projected increases in motor traffic (with attendant increases in the external costs described, not least with regard to your Government’s commitment to Net Zero) will require disincentives such as significantly increased costs of driving to the user.

So how much should the cost of motoring go up by?

Ideally you should announce a commitment to introduce methods of charging drivers in urban areas (where congestion poses a particular problem) by enabling local authorities to use schemes such as Workplace Parking Levies and above all Pay per Mile Smart Driver Charging. As your Cabinet colleagues can tell you, the issue of charging drivers in urban areas (under names such as “Road Pricing”) has been discussed by civil servants and academics for some 60 years.

In the first instance, there are two specific areas where taxation should be increased:

Electric Vehicles (EVs)

Due to Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) cars and vans being replaced with EVs, from expected revenues of £24.4bn from fuel duty in 2024-25, a halving is projected by the 2030s, and receipts will be close to zero by 2050. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility “This is an average £15.5bn a year lost in fuel duty receipts, driven by the assumption all new cars and vans will be zero-emission by 2035 and new HGVs [heavy goods vehicles] by 2040…”

However, replacing revenue lost by the switch to EVs should not be the only, or indeed main, reason for such taxation. Don’t forget that costs to society of congestion, health disbenefits to users, danger and collisions, space consumption etc. for EVs are the same as for ICE cars and vans. Also the main advantage of EVs – lower greenhouse gas emissions – does not mean that the greenhouse gas emissions from EVs and associated measures are zero, as explained here.

Therefore, we suggest that rather than the 3p per mile charge being discussed (raising some £250 p.a. per car/van), an amount at least 3 times higher should be considered. 3p is utterly inadequate for making drivers reconsider making journeys by car, and does not begin to cover the external costs of driving, even with the fuel being clean electricity. If this suggests that drivers may delay moving to EVs from ICE vehicles, the answer is to raise the cost of using ICE vehicles.

Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) cars and vans

In the first instance we suggest that you cancel the freeze on the Fuel Duty Accelerator brought in by the Conservative/Lib Dem government in 2011. At present the average car/van driver pays £600 p.a., which is insufficient to either encourage drivers to make journeys by more sustainable and healthy modes, to counter the external costs described above, or even to encourage use of more fuel-efficient vehicles.

Drivers should also be informed that they have not “paid for the road” (often citing a “Road Tax” which has not existed since 1937): this is not just necessary as part of the justification for highlighting the problems due to driving on society as a whole, but to address the prejudice of all too many drivers that they “own the road” and have more right to be there than pedestrians or cyclists.

After unfreezing the Fuel Duty Accelerator, there can be further increases in duty on petrol and diesel: you can show that this would reduce the prospective increases in motor traffic, cut the external costs associated with this, address some of these costs, and also raise much-needed revenue.

CONCLUSION

We hope this demonstrates that significantly increasing the cost of motoring, primarily through pay-per-mile for EVs and raising the price of petrol and diesel fuel is justified and necessary.

Costs of driving to society as a whole, in terms of public health and the local and global environment, should be seriously considered in such discussions: we need to spend time thinking what driving costs other people and the wider society, rather than just the user of the vehicle.

You will also be able to raise much needed revenue, and we trust that you do so by, in the first instance:

- Placing a 10p per mile charge on electric (EV) cars and vans.

- Unfreezing the Fuel Duty Accelerator.

Dr Robert Davis, for the Road Danger Reduction Forum, 17th November 2025